Uncovering the Layers of Unconscious Bias is the Journey of a Lifetime

This month we celebrate LGBTQ Pride and the end of legalized slavery on Juneteenth in the midst of increasing political turmoil and what seems like rising levels of intolerance. In this piece, June Wilson, Executive Director emeritus of the Quixote Foundation, reflects on the value of uncovering and examining unconscious bias, shining the light on how other funders can do the same.

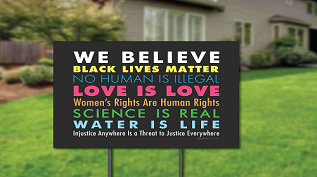

Walking in my neighborhood on a rare rain-free spring day in Seattle, I noticed a rainbow-colored yard sign with the words:

WE BELIEVE

BLACK LIVES MATTER

NO HUMAN IS ILLEGAL

LOVE IS LOVE

WOMEN’S RIGHTS ARE HUMAN RIGHTS

SCIENCE IS REAL

WATER IS LIFE

INJUSTICE ANYWHERE IS A THREAT TO JUSTICE EVERYWHERE

(credit: Signs of Justice)

I was moved. Each line a powerful declaration and manifestation of belief. Each line an invitation to contemplate the perspective of others as well as the multiple expressions of myself. I am an African American whose Irish and Choctaw ancestry are known but remain unknowable to me. I am an Artist, Organizer and Philanthropist, practices through which I make a living. I am a Woman, whose roles as mother, daughter, sister and partner, shape the essence from which I make a life. I am a Christian, who loved a Muslim and is now engaged to an Atheist informing the values and moral codes that guide me. These identities and connections inform who I AM and my view of the world.

As I walk, block after block, I see different versions of the same sign. My attention shifts to a common response to the “Black Lives Matter” manifesto, “but all lives matter.” I become irritated, muttering to myself, “there is no negation or insinuation that other lives don’t matter, it’s simply a declaration that Black lives do matter.” As I walk, my mood shifts from irritation to rage, then I hear the words of my colleague Zarina Parpia say, anger is often an emotion that arises in meditation. Notice it. Embrace it. Let it go if you can. As walking is my preferred mode of meditation, I use her words to notice my reaction and work to release my attachment to it; with some success I move on with the day.

Several weeks later, I heard the address by New Orleans’s Mayor, Mitch Landrieu to his city on their decision to remove four prominent Confederate monuments. Landrieu spoke about our nation’s history of slavery and its impact. He acknowledged the ways in which we privilege and uphold white supremacy. His words reminded me that race is a construct, built so well that the concept of whiteness is unseen. Built so well, that the statement “Black Lives Matter” is an affront while confederate monuments in our midst go ignored.

Taking the Blinders Off

As Landrieu spoke, I wondered if the white supporters of the monuments heard his words as an opportunity for conversation, healing and change, or as a betrayal by him. My thoughts again returned to the signs in my neighborhood. As I reflected on each line, I realized that I hadn’t seen the phrase, “Love is Love” as a reference to gay love – ugh! I kicked myself, acknowledging my heterosexist worldview and realizing the similarities between my unconscious bias around sexuality and the unconscious biases of those blind to their white privilege.

Taking a stroll down memory lane, I remembered the deep unspoken homophobia in the black community of my youth. Growing up, my father made sure that my brothers knew how to fight and stand up for themselves, proclaiming “there are no sissies in this house.” My nephew, at sixteen, unable to fully be himself in our family, ran away. He returned at eighteen, as an adult, now free to express himself openly as a gay man. A few years later, he was diagnosed with HIV/AIDS, and died at twenty-two. The following year, we received a call from my oldest brother. He too was diagnosed with HIV/AIDS. He died from its complications within the year. Losing two family members to AIDS devastated our family. We paid a high price for our homophobia, and yet there was no collective epiphany, recognition or acknowledgement of our bias. Only as I entered the dance community where gays and lesbians became my dearest friends, colleagues and lovers, did I slowly begin to remove my homophobic blinders.

It would be ten years before I understood my bias and another ten before I learned to see past it. And still I don’t always see clearly, as when I missed the meaning of “Love Is Love.”

The Journey of a Lifetime

Uncovering the layers of unconscious bias is the journey of a lifetime. I am only now able to openly and honestly share this story because of the racial equity work I spearheaded at Quixote Foundation. That work was born out of my realization that as the Executive Director and Board member of the foundation, where I clearly held positional power, I felt and acted as if I had no authority. It was a profound epiphany that emboldened me to seek out understanding and change.

Over the course of two years, in monthly multi-day facilitated meetings with staff, board and consultants, we discussed racialized power and privilege, unconscious bias and structural racism, and how those forces influenced our decisions, practices, and engagement with our grantees. We examined the structural, organizational, and personal aspects of racialized power. Managing the personal became easier when we incorporated reflective practices such as somatic embodiment and meditation into our training. Yes, we approached equity by starting with race, largely because of my leadership; however, the path to understanding unconscious bias, power, and privilege can begin from any starting point. The key is to start; the value is in the practice.

Once the journey begins, others will point out new unrecognized biases. When this happens, I find that instead of defending, I must stop, breathe and let myself sit with suffering. I feel the pain, knowing this too shall pass. I call on gentleness and forgiveness to surround me. I reach out to those I trust and respect for help. Not help to be right, but help to broaden my perspective.

I believe that as more of us follow the road signs that point “this way to transforming bias,” we will find way stations along the path reassuring and guiding us. Seeing the signs in my neighbors’ yards served as my way station, as did hearing Mitch Landrieu’s speech. They provided a moment to slow down and reflect upon the work I’ve done, the distance I’ve traveled and the journey still ahead. They remind me to ask what else am I missing? What work remains and where do I need help? Who can assist me, who can I assist?

There are signs all around us. Will we heed them and wake up, or just walk by?