Avoiding Avoidance: Managing Healthy Family Conflict

Avoiding conflict can often seem like the easiest path to take, but if families are to truly practice effective family philanthropy they must deal with conflict head on. Tony Macklin outlines how families can better approach this issue.

Disagreements between two or more people are about what they want to happen next. The participants can typically resolve the dispute without bringing other people into the conversation.

Conflicts, however, are more systemic. They involve multiple underlying issues, longer timeframes, and complex family dynamics. Participants often have very different perceptions of the situation and each other’s intentions. Conflict can involve active fighting, passive avoidance, or a mix of both.

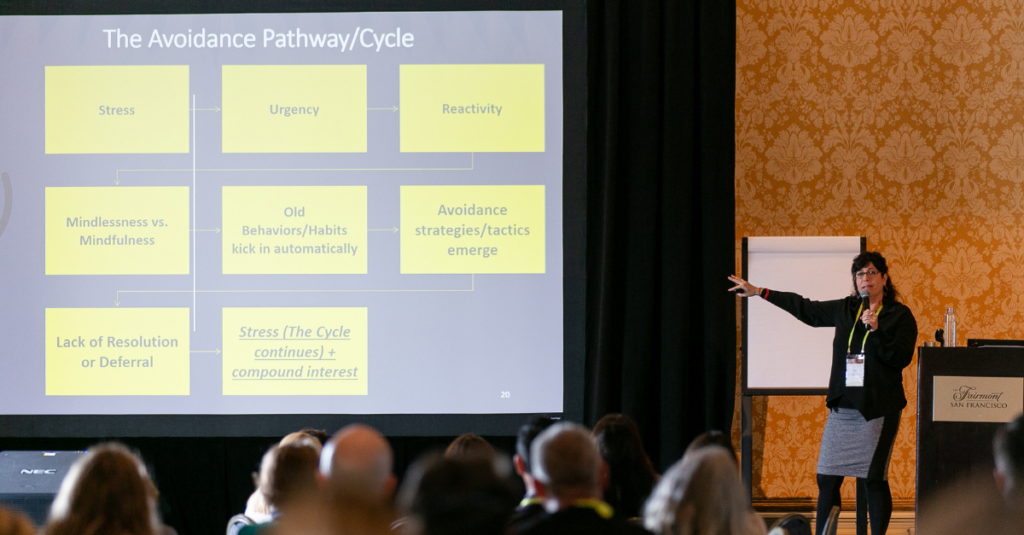

Disagreements and conflicts are inevitable in families, teams, and boards. At NCFP’s 2022 National Forum, Dr. Rebecca Trobe led a workshop on managing conflict more productively. Three of her many recommendations stood out for me.

Dr. Rebecca Trobe delivers a talk on avoiding avoidance at the 2022 NCFP National Forum.

One: Avoid Avoidance

Hoping to avoid disagreements and conflicts is understandable. We’re wired to protect ourselves and minimize stress and perceived sources of harm. But that natural inclination can turn into actively avoiding negative feelings, refusing to acknowledge problems, or fixating on positive thinking.

Even if well-intentioned, those choices have negative consequences. For example, they dismiss or demean another person’s hurt, sadness, or other negative emotion. And they can send the message that the other person is doing something wrong for feeling a certain way or is to blame for a circumstance out of their control.

Ultimately, avoidance of conflict damages a family’s ability to work together productively and be welcoming of new viewpoints and members. Trobe called that level of avoidance “emotionally expensive,” which means there will be less emotional strength and goodwill to create philanthropic impact.

To avoid avoidance, family or group members need to lean into emotional agility individually and create psychological safety collectively.

Two: Lean Into Emotional Agility

Author and psychologist Susan David coined the term emotional agility. Practicing emotional agility asks you not to be immediately hooked by a negative emotion in yourself or others. Instead, you should:

- Show up—face your and others’ thoughts and feelings with curiosity and acceptance instead of judgment. Emotions are important indicators of things you or they need or care about.

- Step out—purposefully detach from the emotion, treating it as one of many sources of information for decision-making. Try to identify different vantage points on a situation and put the emotional response into perspective.

- Walk your why—return to your core values and principles to decide your next actions.

- Move on—make small shifts to align your mindset, motivations, and habits with your core values. You’ll strive to respond thoughtfully instead of reacting quickly.

Following those four steps isn’t always easy. But when you do, you can positively influence a group even if you aren’t the leader. And if you are facilitating or leading a group, Trobe said practicing emotional agility allows you to build a culture of psychological safety in a group so that it doesn’t avoid healthy conflict. It also helps you recognize and name sources of conflict early and identify opportunities to repair the conflict.

Creating psychological safety is an important part of managing conflict.

Three: Create Psychological Safety

Psychological safety is a shared belief that group members will not embarrass, reject, or punish each other for speaking up. On a personal level, you can be yourself without fearing negative consequences to your self-image, status, or career. Trobe outlined four stages of psychological safety originally described by leadership development consultant Timothy R. Clark:

- Inclusion safety—you feel safe to be yourself and are accepted for who you are, including your unique attributes and defining characteristics.

- Learner safety—you feel safe to ask questions, give and receive feedback, experiment, and make mistakes.

- Contributor safety—you feel safe to make a meaningful contribution of your skills and abilities.

- Challenger safety—you feel safe to speak up and challenge the status quo when you see an opportunity to change or improve something.

Successfully creating a culture of psychological safety isn’t the same as creating a comfortable space which can become another means of avoidance. Instead, it creates a brave space that allows us to be candid, take risks, and have productive and respectful disagreements. Within that brave space, we hold ourselves accountable for our actions and for our part in creating psychological safety for others.

Family business consultant Tsitsi Mutendi believes that psychological safety is essential for good family governance. She notes that family leaders can easily overlook the stages of psychological safety. But if they do so, governance documents become “a list of rules instituted by the powers that be which will only lead to conflict at a later stage because there was no full honest participation by all members of the family.”

“Psychological safety at work doesn’t mean that everybody is nice all the time. It means that you embrace the conflict and you speak up, knowing that your team has your back, and you have their backs” – Center for Creative Leadership

Effective Family Philanthropy

Emotional agility and psychological safety aren’t easy to sustain in a family. They need persistent personal and group attention backed by thoughtful facilitation, a set of collective values or principles, and a written code of conduct for meetings and decision-making. But Trobe noted that anyone in a family, or on a foundation’s board or staff, can model the behaviors and mindsets and find allies who want to improve the family’s dynamics and culture.

Emotional agility and psychological safety are fundamental to the principles of effective family philanthropy. Practiced together, within the family and in its relationships with others, the two behaviors:

- Create expectations of healthy, trusting relationships.

- Open the door for a culture of inclusion and belonging and for practices that lead to equity.

- Create and reinforce a sense of mutual accountability.

- Foster a culture of personal growth and continuous group learning.

Any blog post or article can only scratch the surface of a topic like managing healthy family conflict. The resources below provide additional guidance. And, you can reach out to NCFP’s staff or me to learn about experienced coaches, facilitators, and advisors.

Resources

Avoiding avoidance:

- Avoiding Avoidance: Managing Family Dynamics (Session Slides)

- Avoiding Avoidance: Reflective Exercises (Session Worksheet)

- Family Dynamics (NCFP Content Collection)

Emotional agility:

- Understanding emotional agility (Deloitte podcast)

- The gift and power of emotional courage (Susan David’s TED Talk)

Psychological safety:

- Building a psychologically safe workplace (Amy Edmondson’s TEDx Talk)

- What Is Psychological Safety at Work? How Leaders Can Build Psychologically Safe Workplaces (Center for Creative Leadership)

- Psychological safety and the family business (Tsitsi M. Mutendi)

Tony Macklin is a Senior Program Consultant at the National Center for Family Philanthropy (NCFP)